Ottonian, Not Ottoman!

As the practice of Christianity began to expand throughout all over Europe, depictions of religious interactions and their stylistic representations varied in detail, but maintained for the most part similar in symbolic meaning.

Otto I Presenting Magdeburg Cathedral to Christ represents a shift towards increasingly using biblical figures along side rulers to show a leader’s power and divinity in the Early Medieval period. This ivory plaque is part of a series illustrating Ottonian ideology, which was firmly rooted in the connection between Church and State. It was part of a decoration for an altar presented to the Madgeburg Cathedral on its dedication in approximately 968 CE. The plaque was likely to have been crafted in Milan, Italy, which at the time was an imperial center and an artistic hub. Created out of ivory, this plaque shows a juxtaposition of Carolingian artistic traditions and classic Byzantium characteristics. For example, the fact that the plaque was made out of ivory shows its value and significance, as well as it allows for uncomplicated figures to be carved where they are giving emphatic gestures. There is a geometric style background, creating a checkerboard pattern which does not provide any contextual clues as to where Otto I was presenting the Magdeburg Cathedral to Christ. This kind of pattern, however, keeps the focus on the religious exchange between Otto I and Christ.

Furthermore, the scene depicts Otto I presenting a model of the Magdeburg Cathedral to Christ and St. Peter in order to obtain their blessing. The way the figures are arranged with each other reveal a hierarchy of scale such that the emperor, Otto I, is shown small and doll-like, which was done in such a way to show that he is a humble servant to Christ. Also note that the saints and angels depicted are larger than Otto I, but smaller than Christ. This not only creates a hierarchy of scale, but also represents a hierarchy of religious influence and power at the time. We see that that despite Otto being created in a much smaller scale, he is embraced by the patron saint of the St. Maurice church while he passes off the basilica to Christ. The fact that the patron saint of the St. Maurice church was a prominent military commander reveals again the deep connection between State and Church during the Early Medieval period.

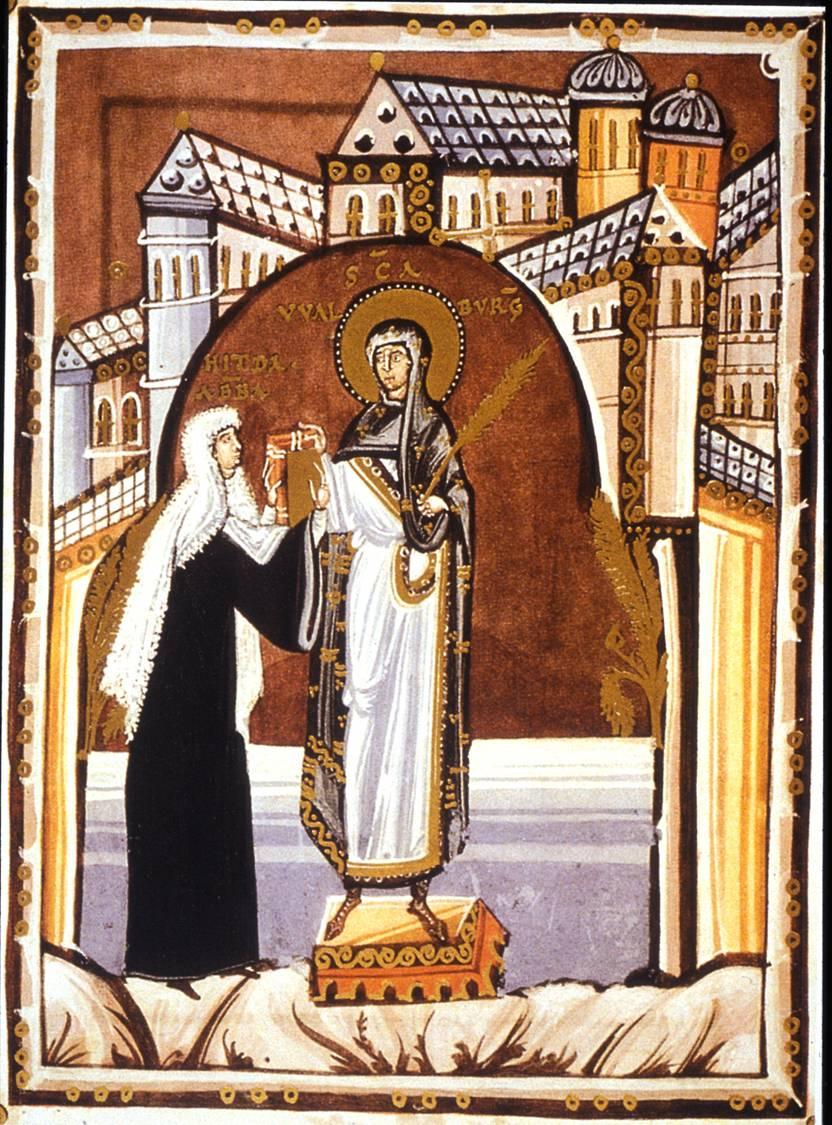

As we move farther during the Early Medieval period, we see a change in style where religious scenes are not only being carved for decoration, but being drawn for elaborately decorated books such as the Presentation Page with Abbess Hitda and St. Walpurga. The difference between these two pieces is not only that one is colored and on paper and the other is carved out of ivory, but also how they depict their various figures in relation with religious figures.

This piece was a page from the Hitda Codex and part of a Gospel book made in the Early Medieval time period for Abbess Hitda of Meschede, which was a women’s monastery in Westphalia, Germany. Instead of just a mix of Ottonian and Byzantium styles like the plaque, the presentation page shows a very distinctive local style where a sense of religious fervor runs throughout the drawing. It is very stylistic where the figures are fairly flat and lack great depth, but a sense of distance is created between the convent buildings and the two figures.

Here, an abbess, dressed in a black gown and while laced veil is offering the Gospel book to St. Walpurga, her convent’s patron saint. While the rest of the convent is shown in the background in a very angular architectural format which draws the eyes down towards the Abbess’ interaction, they two figures are standing on rocky, uneven ground. This is meant to represent a Holy Ground, separated from the rest of the convent; this is known through the huge arched aura surrounding the Abbess Hitda and St. Walpurga.

Size and position are also relevant in this presentation page because it shows a shift in gender relations. For example, the Abbess Hitda is positioned on St. Walpurga’s right which was typically a spot for a male to stand. Standing on his right illustrates her authority and equivalence of power to men, which creates a greater image of spiritual strength on the page. Not only does standing on St. Walpurga’s right show her authority, but also the mere action of presenting the gift to him show that she is the sole authoritative channel of access to the patroness. And the fact that the saint is accepting a gift from the woman shows that he respects her authority and invests Abbess Hitda with the power and influence needed.

Stokstad, Marilyn. Art: A Brief History. Fourth Edition. (Prentice-Hall, 2009)

Help Received: Class notes/GoogleDoc/GoogleImages, Textbook, other online resources