Ethics: the prinicples of conduct governing and individual or group1

Whenever there is an outbreak of an infectious disease decisions must be made on how best to deal with it. If there is not much known about the disease, research on it may ensue– this may also be the case for older diseases that still are a bit of a mystery to the world. Whether treating the infectious disease or researching it, issues may arise with the ethicality of how the situation is handled. Is there a bias against a population– due to race, ethnicity, gender, social status, or otherwise? Are the afflicted being treated for the disease properly? Are they informed on all of their options? Are they informed on what they may be subjected to? What are the obligations of researchers to the study community? Are risk factors associated with the study/disease mitigated? Is informed consent an on-going process or a one-time stamp of approval?2 These are all points that need to be considered when making decisions that could seriously impact human lives. Through history, there have been cases where the answers to these questions reflect poor choices made resulting in ethical issues.

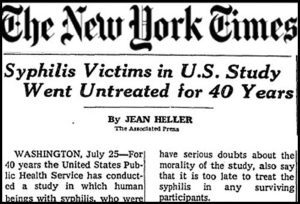

In Macon County, Alabama of 1932, the United States Public Health Service initiated the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the African American Male. This study was supposedly meant to investigate the impact of untreated latent syphillis in the African American male population of the area. However, this study made false promises for special treatments– which turned out to be unanesthetized spinal taps conducted to test the disease’s neurological effects and not to treat the disease– and they continued to withold treatment from the subjects even after penicillin came into use against syphilis in 1947.  Researchers told subjects they had “bad blood” instead of telling them they had syphilis, and they did not tell the subjects about the course of the disease or its treatment. Subjects were kept in the complete dark on what was happening to them and what could or could not be done about it.3,4 The Tuskegee Study only targeted African American males in a rural and underprivileged area of the country, and it only ended after 40 years, when journalists made the study and its practices public.3,4,5

Researchers told subjects they had “bad blood” instead of telling them they had syphilis, and they did not tell the subjects about the course of the disease or its treatment. Subjects were kept in the complete dark on what was happening to them and what could or could not be done about it.3,4 The Tuskegee Study only targeted African American males in a rural and underprivileged area of the country, and it only ended after 40 years, when journalists made the study and its practices public.3,4,5

This study was unethical in numerous ways. Researches denied subjects their right to full, informed consent. They denied subjects proven, effective treatment. Furthermore, they denied them the choice of recieving antibiotic treatment or not. Selection of study participants was biased and racially driven. On top of all of this, the study was poorly conducted. Individuals in the control group were moved to the subject group if they contracted the disease, goals of the study frequently changed without notifying participants, and there were bad protocols.3,4,5 Research participants deserve to know exactly what they are signing up for. They should not be led on by false promises and lies. Changes to the program should be brought before each subject and they should be able to withdrawl from the study at any point. These basic rights were witheld from the subjects of the Tuskegee Study– which is why the study was so unethical.

Researchers rationalized these decisions and this behavior to justify continuing the study and to defend their actions. In regards to the matter of penicillin treatment, researchers argued that there was not sufficient data on the effectiveness and both the long and short term effects of the drug.4,5 It is argued by the uniformed that this study did not violate rules of informed consent merely because ‘such standards did not exist in the 1930s’ and that this behavior was ‘common’ at the time of the study, so it would not have been unethical.5 During the 1940s, amongst the turmoil of World War II, Nazi experimentation was widely known of and looked down upon. When the Tuskegee Study’s practices were compared to the Nazi experiments their rationalization was that “…they were Nazis, we’re not.”3

Unethical studies have a higher potential for negative consequences than ethical studies. In the case of the Tuskegee Study, because of racist beliefs about African American and their behaivors, their community was targeted for an unethical study that left them vulnerable to a communicable disease with severe health reprecussions.4 After the practices of the study were exposed, there was an increase in mistrust of the medical profession among the African American community. They became more wary of health care professionals and their investment in their health- leading many to stop visiting the doctor and only putting their community at higher risk for health complications.6 In recent years, treatment for an outbreak of tuberculosis was hindered by mistrust of medicine and professionals. This mistrust was feed particularly by the damage done with the Tuskegee study.7 When unethical studies are carried out, not only do they pose an immediate and dangerous risk to the health of their studies, but they also put future generations at risk as mistrust spreads and takes root in targeted communities.