Emerging infectious diseases are infections that have recently appeared within a population or those whose incidence or geographic range is rapidly increasing or threatens to increase in the near future1

Emerging and re-emerging diseases are an increasingly more important and pressing issue in the world today. Zoonotic infections are one source of these emerging and re-emerging diseases. Zoonotic infections (or zoonosis) are diseases that jump from animals to humans. Such occurrences are also an example of spillover, which results when a reservoir population with a high prevelance of a pathogen comes into contact with a novel population.2 When spillover occurs, outbreaks can become pandemics.

Examples of such infections and diseases are:

- Ebola: Non-human primates are the believed source of human infection3

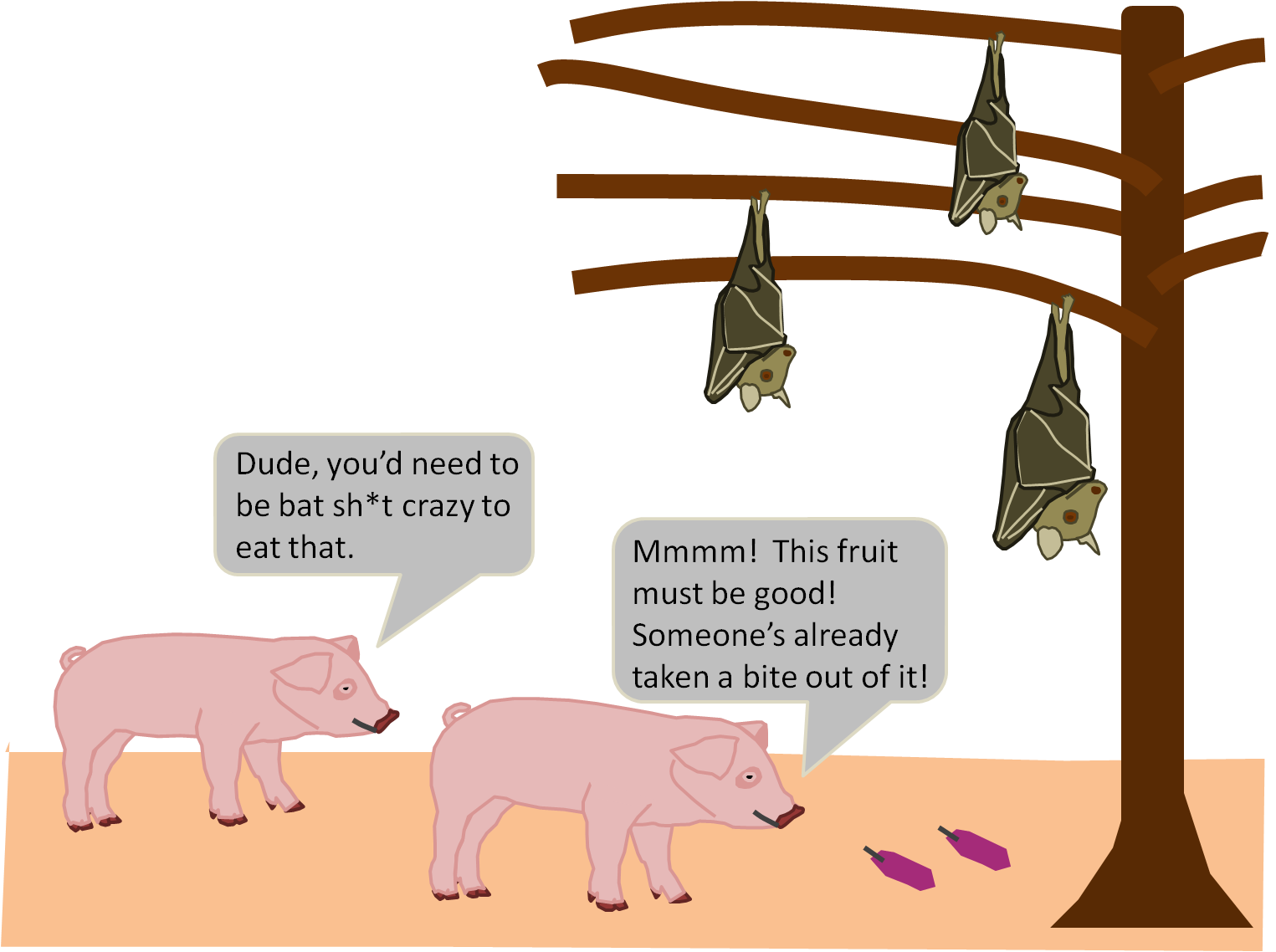

- Nipah: Transmitted from bats to humans and to intermediate hosts like pigs4

- Cat Scratch Fever: Cats and occassionally fleas and ticks may transmit the disease to humans5

New means of travel and transportation over the past two hundred years have certainly contributed to the spread of infectious diseases. The invention of trains, cars, and airplanes have allowed humans to travel far and wide easily and quickly. These modes of transportation allow not only humans to travel the world, but they also allow any infectious agents a human may be harboring to travel along with them and spread to new regions and populations. When an infected individual is traveling, for instance, in a plane, they are in a confined space with many other people. Those other, uninfected individuals are now at risk of exposure to the infectious agent. If they get infected, they then have the capability to pass the agent onto others once they leave the flight. Poor practices in sanitation and personal health practices also may contribute to the occurrence of major outbreaks. For instance, some areas of the world, especially in third world countries, lack sufficient sanitation means and pracitces, leaving them exposed to the risks associated with unclean water and with waste. Furthermore, individuals that don’t exercise certain health practices, such as washing their hands often, covering their coughs and sneezes, etc., are more likely to pass on any pathogens they may be carrying to others.

When epidemics do break out, humans are typically slow to respond. If there are a lack of resources and funds, the measures needed to contain and stop the spread of disease are delayed and not implemented until the epidemic has had a chance to do a significant amount of damage. The public may also be resistant to work with health officials and to practice the necessary health practices needed to stop the epidemic.6 Countries that are unaffected by an epidemic may be hesitant to extend help out of fear of the virus and the implications of the outbreak as well. Additionally, the role that politics and social behaviors play in the decision making process of crucial responses may hinder the implementation of the appropriate course of action. These factors contribute to what many call ‘outbreak culture.’

One of the biggest pandemics to affect the world, and especially the United States of America, is influenza. In 1918, the Spanish Flu wrecked the human race through out the world. Influenza is a versitle virus that has the capability to change strains many times. As a protective measure in 2005, the United States Department of Health and Human Services developed a plan in the event of another flu pandemic. Additionally, they created three tools to guide the nation’s response to pandemic: the Pandemic Intervals Framework, Influenza Risk Assessment Tool, and the Pandemic Severity Assessment Framework.7 Christine Blackburm et al., makes a compeling argument in her article for The Conversation that the United States is not prepared for the next pandemic.8 She notes that antibiotics are sorely over used and also misused throughout the country; there is a risk associated with the global supply chain in the event pandemic breaks out; there is a lack of leadership at the heart of the American government, in the White House that would be responsible for quick, decisive action in response to pandemic.8 To overcome these obstacles, the United States should place this threat as a higher priority. The government needs to strengthen its international, global efforts to coordinate response actions, be aware of weak links in the supply chain and develop diverse ways to reduce the risks posed, and there needs to be a better understanding of how the health of the environment and animals plays a role in human health.8

References

1https://www.bcm.edu/departments/molecular-virology-and-microbiology/emerging-infections-and-biodefense/emerging-infectious-diseases

2https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spillover_infection

3https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/ebola-origins-reservoirs-transmission-and-guidelines/ebola-overview-history-origins-and-transmission#transmission

4Spillover Film Worksheet

5https://www.healthline.com/health/cat-scratch-disease#causes

6https://www.statnews.com/2018/12/17/outbreak-culture-can-derail-effective-responses-deadly-epidemics/

7https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/national-strategy/index.html

8https://theconversation.com/three-reasons-the-us-is-not-ready-for-the-next-pandemic-100799